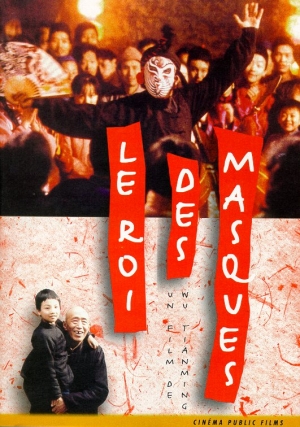

Le Roi des masques / Bian Lian

(Wu TIAN-MING, Hong-Kong - 1997)

En partenariat avec "Ethnologie et Cinéma"

Mercredi 16 octobre 2013 à 20h

Salle Juliet Berto - Grenoble

Wu TIAN MING est né en 1939 à San Yuan, dans le Shaanxi-Gangsu-Ningxia, à cette époque enclave communiste dans la Chine nationaliste. Enfant, il suit la vie itinérante et mouvementée de son père, chef des partisans.

C'est en voyant le film du cinéaste russe Dovjenko "Poème de la mer" en 1958 qu'il se prend de passion pour le cinéma. Deux ans plus tard, il abandonne ses études universitaires pour suivre les cours du studio cinématographique de Xi'an. Il travaille ensuite un an aux studios de Pekin aux côtés de l'acteur et réalisateur Cui WEI où il co-réalisé deux films avec Ten WENJI ("Les trémolos de la vie" en1979 et "Une seule famille" en 1980). Il rencontre le succès avec "La vie" réalisé en 1984.

Il devient directeur des studios de Xi'an et réalise "Le vieux Puits" en 1987. Il fait alors travailler les plus importants réalisateurs dits de la "cinquième génération" Zhan YIMOU ou Chen KAIGE, auxquels il a ouvert la voie.

A la fin des années 80 le studio de Xi'an, jugé trop novateur est menacé de purge. Lors de la violente répression des mouvements étudiants sur la place T'ien an Men en 1989, Wu TIAN MING est à New-York. Il décide de rester aux Etats Unis où il enseigne l'histoire du cinéma chinois à l'Universite de Davis dans l'Illinois.

Il rentre en Chine en 1994 et s'installe à Hong Kong en 1995. C'est là qu'il réalise "Le Roi des masques",

film auréolé de plus de 30 récompenses de par le monde, dont celui du Meilleur film en 1997 au Festival de Venise.

Synopsis

En Chine centrale, au début du siècle, un vieux maître de l'opéra a choisi de vivre dans la rue, en saltimbanque. Il est montreur de masques et son habileté à en changer devant des spectateurs qui n'y voient que magie l'a fait surnommer le roi des masques. Le vieil homme souhaitant transmettre son art, décide d'adopter un garçon, Gouwa. Il se prend d'affection pour l'enfant qui suit son enseignement avec un vif intérêt. Mais un jour le vieil homme découvre que Gouwa est une fille.

"Le Roi des masques met en scène une tradition chinoise ancestrale : l’opéra. Deux personnages incarnent deux grandes écoles : l’acteur Maître Liang, celle de l’opéra de Pékin, et Wang, celle de Sichuan. Le film de Wu Tian-Ming interroge la responsabilité de l’artiste face aux injustices de la société. Comment dépasser les vieux adages, les crispations traditionnelles, les superstitions archaïques ? Comment – pour reprendre l’image de Liang – apporter un peu de chaleur sur cette terre froide ? En artiste chinois, Wu Tian-Ming use du détour pour mettre en jeu la place de l’art dans le monde. (…)

Le sujet du film est poignant : comment le vieux maître des masques parviendra-t-il à accepter de transmettre son art à un enfant acheté qui n’est rien qu’une fille ? Wu Tian-Ming se fait ici le témoin d’une tradition chinoise qui perdure à l’heure actuelle : "bian lian", l’art des masques, ne se transmet au grand jamais à une fille. Ce thème, il l’aborde de façon réaliste mais également poétique. Le cinéma chinois de la Quatrième génération dont Wu est un éminent représentant ne se permet d’aborder les problèmes sociaux qu’avec la distance du film historique. Nous sommes donc au début du siècle, dans une période troublée, inquiète et pauvre, où la vente d’enfants est monnaie courante, si l’on peut dire. La séquence du marché aux enfants est caractéristique de son traitement du réel : poétique mais sans concession. Nous ne savons pas exactement où se déroule l’action : le montage – par un fondu enchaîné -– nous conduit d’emblée au cœur de cet espace insolite.

Wang est abordé immédiatement par une enfant qui lui offre ses services comme servante. Elle se jette à ses pieds. Dure réalité de cette époque : pour assurer un avenir à ses enfants, on les donnait ou vendait comme domestiques. La caméra suit le vieil homme mais dans la profondeur de champ s’esquissent d’autres destins tragiques : les enfants sont transportés, poussés, tirés, vendus. La bande-son résonne de cris, de plaintes. Wang traverse cet espace, comme gêné d’en arriver à se trouver là. L’espace fermé est éclairé par le haut, le sol recouvert de paille : atmosphère poussiéreuse. Les divers personnages passent devant la caméra : Wu Tian-Ming n’appuie sur aucun détail, c’est sans pathos qu’il nous laisse entrevoir cette dure réalité. Sous le regard affligé de Wang, nous suivons au premier plan une femme qui peine à laisser sa fille à celui qui l’emporte."

Marie Omont, extrait du dossier pédagogique École et Cinéma, les Enfants de Cinéma.

Tian-Ming Wu was born in 1939 in San Yuan, in the Shaanxi-Gangsu-Ningxia, which at that time was a communist enclave in Nationalist China. As a child his life was an itinerant and exciting one his father wad the head of the the partisans.

It was on seeing "Ode to the Sea" by the Russian film-maker in 1958 that his passion for cinema developed. Two years later, he dropped out of university to follow the course at the X’ian film studios. Subsequently he spent a year at the Beijing studios by the side of the actor director Cui WEI where he co-directed two films ("The Tremolos of Life" in 1979 and "A Single Family" in 1980). Success came with "Life" in 1984.

He became the head of X’ian studios and directed "The Old Well" in 1987. He also helped the the most important directors of the “Fifth Generation’ Zhan Yimou and Ken Chaige by opening doors for them.

At the end of the 80s the X’ian studios were found to be too innovational and were threatened with a purge. At the time of the violent repression of the student movement on Tienamen Square, Tian-Ming Wu was in New York. He decided to stay where he taught the history of Chinese cinema at Davis University in Illinois.

He returned to China in 1994 and moved to Hong Kong in 1995 where he made "The King of Masks" which went on to receive more than 30 awards world-wide including the Best Film at the 1997 Venice film festival.

Synopsis

At the beginning of the 20th century in central China, an old opera master has chosen to live on the streets. He practices Sichuan change art and his ability to change masks without his audience noticing leads to his being nicknamed ‘The King of Masks’. The old man wishing to pass on his skills decides to adopt a young boy, Gouwa. He takes a liking to the child who is keen to learn. One day the old man finds out that Gouwa is a girl.

The King of Masks highlights an ancient chinese tradition, opera. Two characters are the incarnation of the two main schools: The actor Master Liang represents the Beijing school and Wang the Sichuan school. Tian-Ming Wu’s film investigates the responsibility of the artist when confronted with society’s injustices. How to overcome the old adages, traditional tensions, archaic superstitions? How, to use Liang’s metaphor, to bring a little warmth into this cold world?

This is a poignant film about whether the the old master of masks will consent to pass on his skills to a slave child who is only a girl? Tian-Ming Wu uses a Chinese tradition that still endures, ‘bian lian’, the art of masks which is never ever passed on to a girl. He deals with this subject poetically but also realistically. The fourth generation of Chinese cinema, of which Wu is a pre-eminent member only allows itself to deal with social issues through the lens of period films. Thus we find ourselves at the beginning of the 20th century, difficult times, uncertain and poor, when the trafficking of children was common. The children’s market sequence is typical of his representation of reality. Lyrical but not holding back. We are not exactly sure of where the action is taking place. The editing, via a series of dissolves brings us rapidly to the centre of this strange place.

Wang is immediately accosted by a child who throws herself at his feet offering her services as a servant. It was a cruel fact that in those times parents, in order to secure a future for their offspring, would sell or give their children into servitude. The camera follows the old man but in the background we see other tragic destinies playing out. Children are transferred, pushed, pulled and sold. The soundtrack resonates with screams and protestations. Wang crosses this space as though he’s ashamed to have ended up here. The market is lit from above, the ground covered in straw and the air is full of dust, various characters flit past the camera. Tian-Ming Wu does not linger on any particular detail. He lets us see this hard reality without pathos. We see, through Wang’s eyes, the despair of a mother who has to leave her daughter in the hands of the man who has taken charge of her.

Marie Omont - extract from the teaching notes School and cinema, Children and cinema.

![Peur[s] du noir](/cineclub/media/k2/items/cache/2ff2ba0051687eef5ca0459cf942940c_Generic.jpg)